2024 Election: 20-inch nails in Korean democracy’s coffin

In this year’s election, a total of 59 parties are asking for a vote.

Does the biggest-ever number suggest the height of South Korean democracy? I’m a bit skeptical.

How many of them are really serious? I took a count of the number of leaflets included in the official election packet sent by the election commission.

Out of the 38 parties aiming for proportional representation, only 9 parties managed to include their parties’ leaflets in the packet.

Well, printing leaflets for every voters in the nation takes a lot of money. Even if you’re dead serious about the election, your budget may not be so.

So I looked into the election commission website. 15 parties didn’t even bother to submit it digitally.

When Minjoo pushed for the amendment of the election law in 2019, which paved the way for this pandemonium, some “progressive” commentators dismissed the concerns over an election overrun by a torrent of haphazardly established parties.

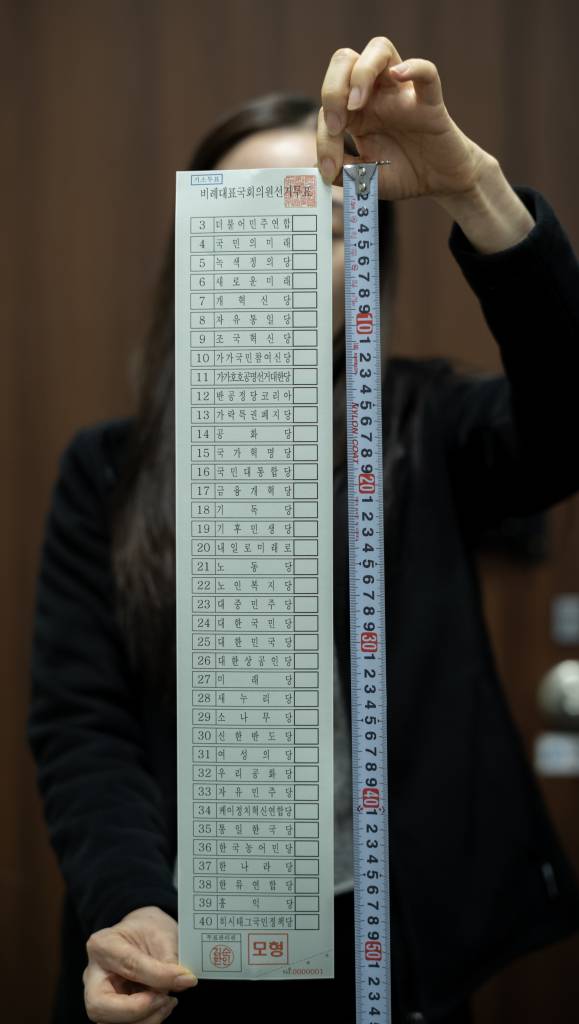

Once again, all proportional representation ballots will be counted manually because voting machines can’t process ballots this long, as they were in 2020, which was the first election since the “election reform.”

Too many joke parties and having to count votes around the clock wouldn’t be a serious harm to democracy themselves. But the true consequences of the reform are.

The election reform accomplished just the opposite of its aim.

It was said the new proportional representation system will improve the diversity of the National Assembly by allocating more seats to minor parties.

But the proposed (and eventually passed) bill had one glaring loophole: satellite parties, which will be technically also minor parties. Critics repeatedly warned from the beginning this will allow the opposite of what the reform sought to accomplish.

Minjoo kept ahead, however, and succeeded with help of the minor parties such as the Justice Party, which soon fell prey to the reform it supported.

First, it will eat up Justice Party.

It didn’t even take much time to see how it unfolds: in less than four months since the bill passed, Minjoo and its satellite party, which it promised not to establish, had the biggest win of all time—180 seats out of 300—in the 2020 election.

Justice Party managed to keep its seats in total—6—last time, but it might not survive this time. Its approval ratings have been below 3% threshold in many polls.

It is hard to understand, with all the issues that had been glaring from the day it was proposed, why the Justice Party voted for the reform bill. Sim Sang-jung, who’s been leading the party for years in practice despite the official titles, appears to be hooked on the idea. (From what I’ve heard from people, Sim tend to put her personal network first in deciding something, rather than her own party.) With her party on the verge of withering away, Sim’s own local constituency is about to ditch her as well—an end she deserves.

Next, representative democracy.

The most critical harm the reform has done is the disruption of representative democracy.

Major parties, for all its flaws and stupidity, tend to take greater care in choosing their candidates. They also tend to take public opinion more seriously when issues are raised on their candidates.

The same can’t be said, however, for satellite parties. They don’t have histories and they don’t have to (and even want to, as they can later join the main party) last long. The primary satellites, which are direct offshoots of the major parties, may be just fine, but when it comes to the secondary satellites—unofficial satellites often formed by those who seek partisan support from voters—the bar is nowhere to be seen.

Gerrymandering the generations

The quality of representative democracy will take another plunge after this year’s election. Cho Kuk, the disgraced former justice minister is leading it.

Mr Cho is truly a fascinating figure: a man of contradiction who commands a cult-like following, I’d call him the progressives’ Trump. Unlike Mr Trump, Mr Cho is already found guilty in previous trials and likely to serve a sentence after the supreme court ruling.

This hasn’t changed his devotees’ mind. His makeshift party is enjoying tremendous ratings in polls—even surpassing the primary satellites in some cases.

Had there been no “reform” in the election law, Minjoo wouldn’t dare to appoint Mr Cho as its candidate: despite the fervent support from Gen X, he is a distrusted figure nationally. Mr Cho’s party has almost zero support from millennials in the polls.

In unexpected twists of events since the election reform, “Minjoo progressives” managed to gerrymander the generations of voters. Minjoo doesn’t have to agonize over whether to include polarizing figures in its roster anymore: just get them set up a satellite party and “lease” its lawmaker for a better ballot position.

(Conservatives will soon adapt: maybe in the next election, we could see Lee Jun-seok coming back with a dedicated anti-feminist satellite party.)

Prosecutorial “reform” taking effect

If we translate the latest polls directly into actual votes, Mr Cho’s party may get up to 17 seats. For a comparison, Democratic Labor Party민주노동당, the most successful progressive party in history, in its brightest days only managed to get 10. Looking at their roster of proportional representation makes me crave for Prozac.

What’s their flagship platform? Finishing the “prosecutor reform.” What does it even mean? Kicking asses of the bad guys dogging Mr Cho and his colleagues, including Hwang Un-ha, former Minjoo lawmaker who was found guilty for interfering the Ulsan mayor election, is the best I can guess.

Speaking of the prosecutor reform, it is now beginning to make a difference:

The political landscape has changed. You’re gravely mistaken if you think conservatives still have the upper hand in South Korean politics. For some reasons including demographic shifts and socio-economic developments, now Minjoo progressives are the dominant force. (If you want to dig deeper, I recommend Cho Gwi-dong’s The Road To Italy.)

The aftermath of the two major “reforms” will have lasting effects on the representative democracy and the rule of law. Minjoo will have to pay the price for this.

But with Pres Yoon campaigning for Minjoo, how can conservatives expect to win?

I already said President Yoon doesn’t care much about approval ratings. But I’d have to say, I didn’t expect him to be this bad at reading the room.

His terrible dealing with the revolting doctors and laggardly responses to his aides’ issues have given Minjoo the higher ground. Although I believe Minjoo’s seat won’t exceed their last election result—180 seats are the theoretical maximum of Minjoo’s support base—the ruling party remaining minority with a president at their side (um… it’s technically true) is a defeat in itself.

Running an election as a ruling party has been rather easy in Korean politics. All you have to do is showing some degree of remorse and promising you’ll get better. Do the kowtow if necessary. Voters love the sight of it.

Alas, Mr Yoon was not only the kind of guy who refused to kowtow to a boss when he’s wrong. He was also the kind of guy refused to kowtow to the public when they’re right.

My biggest miss in my previous write-up was Han Dong-hoon. I expected him to wield his dagger more liberally as the President is so unpopular.

I was wrong. Perhaps Yoon’s remaining three years of term deemed too long to be passed in conflict. Yoon loyalists managed to wring themselves into some of the most convenient constitutes.

The most notable case is Joo Jin-woo, former presidential aide who is running in one of the richest constituencies in Busan. A PPP candidate won by more than 20%p margin in the last election, but this time Joo is trailing behind a Minjoo candidate in polls.

Han does understand that this is going to be a defining moment in his political career, but his previous life as a prosecutor offer little help in how to navigate the dynamics of politics, it seems.

It’s the economy, stupid! (again and again)

The gaping void of “economy” in the campaign is another peculiarity of this year’s election. While Minjoo has been ranting about prosecutors, PPP has been obsessed to the “student activist establishment.”

Don’t we have an economy to fix?

Last year’s GDP growth explains (partly) why Pres Yoon is so unpopular:

(This is my first attempt at producing charts with Python 😎)

Despite the tried-and-true history of Keynesian economics, Pres Yoon never attempted a budget deficit. Why? Because he belongs to the same school as Javier Milei?

More plausible explanations are 1) Yoon doesn’t want any compromise to Minjoo—such as appointing a special prosecutor to the suspicions on the First Lady—as any supplementary budgets will require a cooperation from the opposition who controls the legislative; 2) Yoon is held hostage—for a lack of vision—to finance ministry technocrats who are firm believers of balanced budget.

The polarizing politics that is negligent in people’s actual livelihoods (I think “prosecutor reform” is the most successful culture war product in Korea, which I’ll revisit soon) leaves us little hope for a better future.