The Actor, Nuna-gate, and Bone Broth

A celebrity scandal has exposed the deep-seated “siege mentality” of South Korea’s left. The “nuna” scandal exposes the informal, personalized power structures in the President Lee’s office. The ruling Minjoo Party is milking the martial law incident for too long, risking a public backlash through legally dubious overreach.

Before we descend into this week’s political fray, a brief personal detour: German stollen has been the festive carbohydrate of choice in Seoul for several winters now. Naturally, local evolution has followed: we are now witnessing the arrival of “stollenized” Korean walnut pastry (hodugwaja). I attempted to secure this fusion delicacy multiple times, only to be thwarted by sold-out signs. As ever, the domestic appetite for novelty remains undefeated.

As ever, feel free to send me a note—any feedbacks, or questions are welcome.

—Subin

Cho Jin-woong Scandal: When Tribalism Trumps Justice

Why it matters: A celebrity scandal has exposed the deep-seated “siege mentality” of South Korea’s political left, threatening to fracture the ruling party’s fragile alliance with young female voters ahead of the next election cycle.

Cho Jin-woong—a face recognizable to any consumer of Korean cinema—was quick to announce his retirement after a leading tabloid exposed his past. And the revelations are still unfolding.

This was far from the average celebrity’s teenage indiscretion. The allegations read like a rap sheet from Grand Theft Auto: vehicle theft, kidnapping, and the sexual assault of multiple women—including minors—using the stolen cars. While Mr Cho’s resignation the following day was exceptionally swift, the gravity of the accusations rendered it the only logical move.

Far more extraordinary, however, was the reaction from certain quarters of society. A vocal contingent of professors, lawyers, and journalists decried the “persecution” of Mr Cho, arguing that he had already paid his dues—a punishment that was notably lenient given his age at the time. These defenders share a single commonality: they form the intellectual core of the Minjoo Party’s support base.

It turns out that our Trevor Philips has been a poster boy for the Minjoo establishment’s version of social justice. Kim Ou-joon, the left’s answer to Tucker Carlson, also defended our real-life GTA protagonist, claiming Mr Cho is the victim of a conservative conspiracy. In a flourish of absurdity, he even likened the actor to Jean Valjean of Les Misérables.

This case highlights, yet again, the fierce tribalism of the core Minjoo base. Their moral compass regarding any given crisis seems entirely calibrated by whether the actor in question belongs to their camp. Consequently, we are left with the grotesque spectacle of self-proclaimed human rights activists rushing to the defense of alleged sex offenders.

The “siege mentality” of the 86 Generation (Gen-86) may have helped cement their status as the dominant political bloc of the modern era. However, this same instinct risks alienating the very coalition partners Minjoo needs to retain power. Young female voters have been a crucial ally to the party; watching Gen-86 luminaries canonize a man accused of predatory sexual violence is unlikely to inspire their continued loyalty.

President Lee’s Blind Spot: The Abductee Question

It is a profound embarrassment that a sitting President should appear so utterly unaware of his own citizens held captive in the North. This ignorance is particularly jarring coming from a leader who, mere months ago, declared that “anyone who harms a Korean will be utterly ruined.”

The exchange between President Lee and NK News’s Chad O’Carroll is essential viewing. It offers a revealing glimpse into the President’s demeanor when pinched:

Yet, the inconvenient truth is that the sanctity of citizens’ lives has rarely been a priority for any administration, whether conservative or liberal. We have already witnessed the Moon Jae-in administration maintaining a studious silence even as Pyongyang executed a South Korean citizen and incinerated his body.

Sister Act: The Unscripted Role of “Hyun-ji Nuna”

Why it matters: The “nuna” scandal exposes the informal, personalized power structures that often bypass official vetting in the President Lee’s office—a dynamic that historically precedes major corruption scandals in South Korea.

The Lee administration has gone to extraordinary lengths to scrub Kim Hyun-ji’s footprint from the public record. The President’s Office even reshuffled its personnel structure specifically to shield President Lee’s longtime confidante from a parliamentary audit summons.

Ironically, the maneuver backfired: the very act of hiding Ms Kim only served to broadcast the true magnitude of her clout.

Enter Kim Nam-kuk, the President’s communications aide and former lawmaker, who apparently missed the memo on discretion. In a leaked text message regarding a request for a job favor, Mr Kim casually promised to run the matter by “Hyun-ji nuna“—using the Korean term of endearment for an older sister or female friend.

For all the administration’s strenuous denials regarding Ms Kim’s influence over the inner workings of the state, Mr Kim handed critics the smoking gun on a silver platter. (He has since resigned in the fallout).

To be clear, influence itself is not an indictment. Every leader has advisors. However, this specific brand of shadowy, unofficial gatekeeping is the breeding ground for the sort of corruption and abuse that famously toppled President Park Geun-hye and her “shadow president,” Choi Soon-sil.

South Korean political history teaches us that presidents are rarely undone by sudden, shocking revelations; they are brought down by open secrets. When Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye vied for their party’s nomination years ago, they attacked each other with the very liabilities that would eventually destroy them: corruption for Mr Lee, and the “confidante problem” for Ms Park.

President Lee’s eventual undoing will likely follow this grim tradition. It won’t be a bolt from the blue, but something we have seen all along. Ms Kim, who has stood by Mr Lee’s side for nearly three decades, fits the profile perfectly.

The Politics of ‘Sagol’: Minjoo Milks the Martial Law Anniversary

Why it matters: The ruling Minjoo Party is milking the events of December 3 for too long, risking a public backlash through legally dubious overreach.

Like any culture with a history of scarcity, Korea reveres bone broth. Simmering cow bones is the foundational step of its traditional cuisine; sagol, the byword for this broth, literally refers to the four leg bones of a cow.

However, we often simmer the same bones once too often—driven by poverty or simple inertia—until we are left with a tasteless, translucent swill. In colloquial Korean, sagol has thus become a pejorative—a metaphor for recycling stale content ad nauseam.

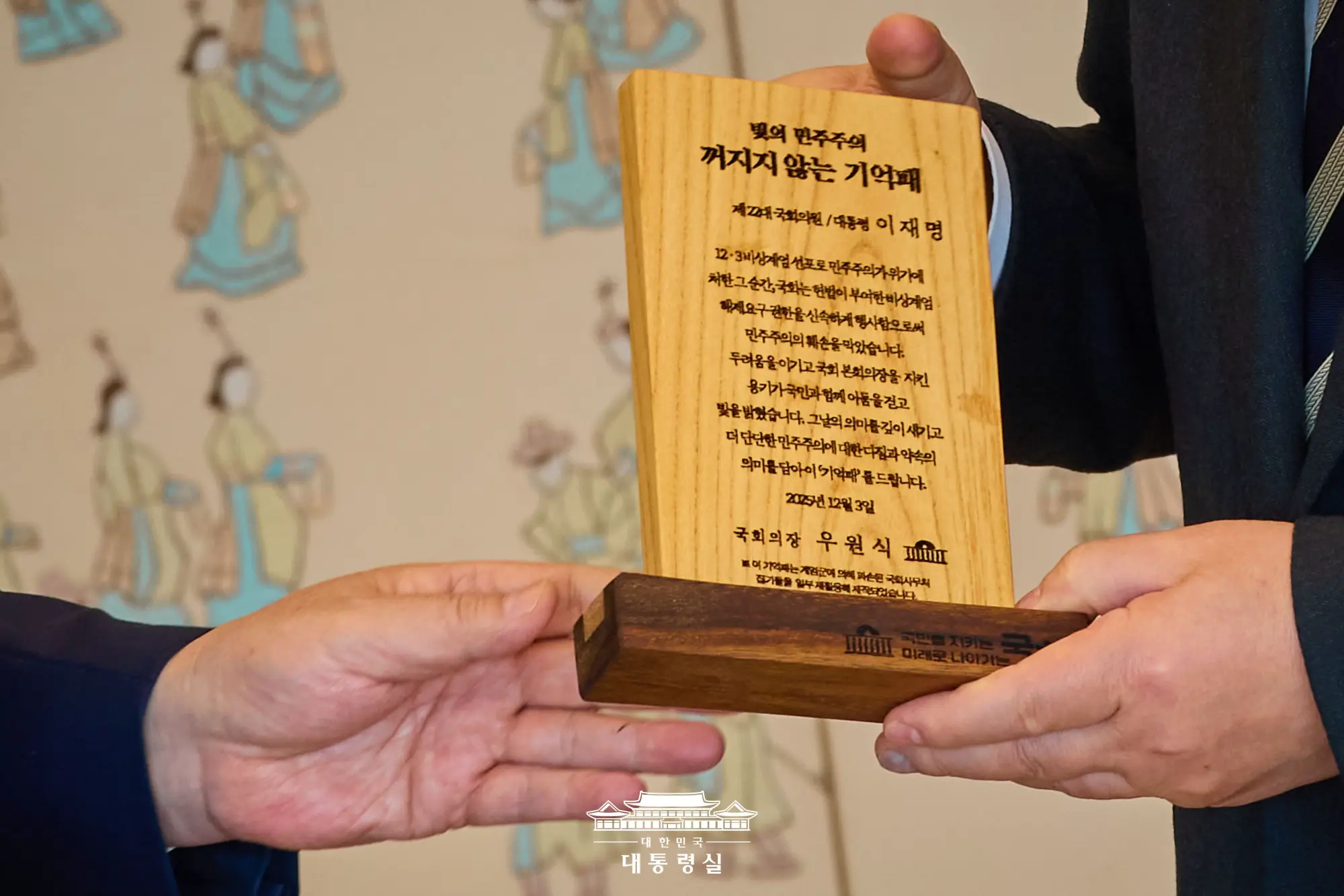

As the first anniversary of the December 3 martial law incident arrives, Minjoo is stewing a pot of sagol seasoned with vacuous slogans like the “Revolution of Light.” (A prime entry for my personal dictionary of K-Cringe, or K-ringe.) The National Assembly Speaker even led a “dark tourism” tour of the legislature, donning the very same coat he wore that fateful night a year ago.

Performative Piety

While the events of last year demand remembrance, I cannot shake a sense of second-hand embarrassment. Apparently, the Lee administration and Minjoo intend to enshrine this event in the pantheon of revolutions that shaped modern Korea, alongside the April Revolution of 1960 and the Gwangju Uprising of 1980.

But was it really a revolution?

Revolutions occur to overthrow an existing order that has lost the capacity to reform itself. In April 1960, the Syngman Rhee administration was corrupt beyond repair; in May 1980, the people of Gwangju revolted against a new military junta, spearheaded by Chun Doo-hwan, that had no intention of yielding to demands for democratization.

What happened on December 3 last year is categorically different. Order was restored in three hours. President Yoon was ejected from office with due process—all within the existing constitutional framework. Not to mention that the “coup” itself was arguably the most farcical flop in modern Korean history.

The only aberration here is Minjoo’s relentless bone broth of rhetoric to seize the moral high ground. And now, they are going further: pushing for a special tribunal dedicated to the “total conviction” of anyone involved in the “insurrection.”

The Legal Quagmire

Contrary to the narrative peddled by Minjoo zealots, it is legally debatable whether the events of December 3 constituted a blanket insurrection. The President has the constitutional authority to declare martial law; the Assembly has the authority to rescind it, which it promptly did.

The question is whether the President followed due process. It appears Mr Yoon did not, but procedural failure points to abuse of power, not necessarily insurrection. However, the mobilization of troops to physically block lawmakers from exercising their constitutional duty to lift martial law does cross the line. On these grounds, I believe Mr Yoon and the top military brass with whom he conspired deserve the harshest possible punishment.

The Backlash

Yet, Minjoo seems more interested in weaponizing the charge to liquidate political opposition. This bizarre push for a separate court betrays their anxiety following the incompetence of the special prosecutors, whose efforts resulted only in a flurry of rejected arrest warrants.

Maximalism in political strife often invites blowback. This proposed insurrection court is a case in point. It is being criticized as unconstitutional and is already riddled with legal flaws—displaying a level of incompetence rivaling that of Mr Yoon’s own cabal. In its quest to “root out insurrectionists,” Minjoo risks galvanizing the very Yoon sympathizers it seeks to purge.

The Republic’s democracy was robust enough to quell the martial law attempt in a few hours. It hardly needs an extralegal institution to finish the job.