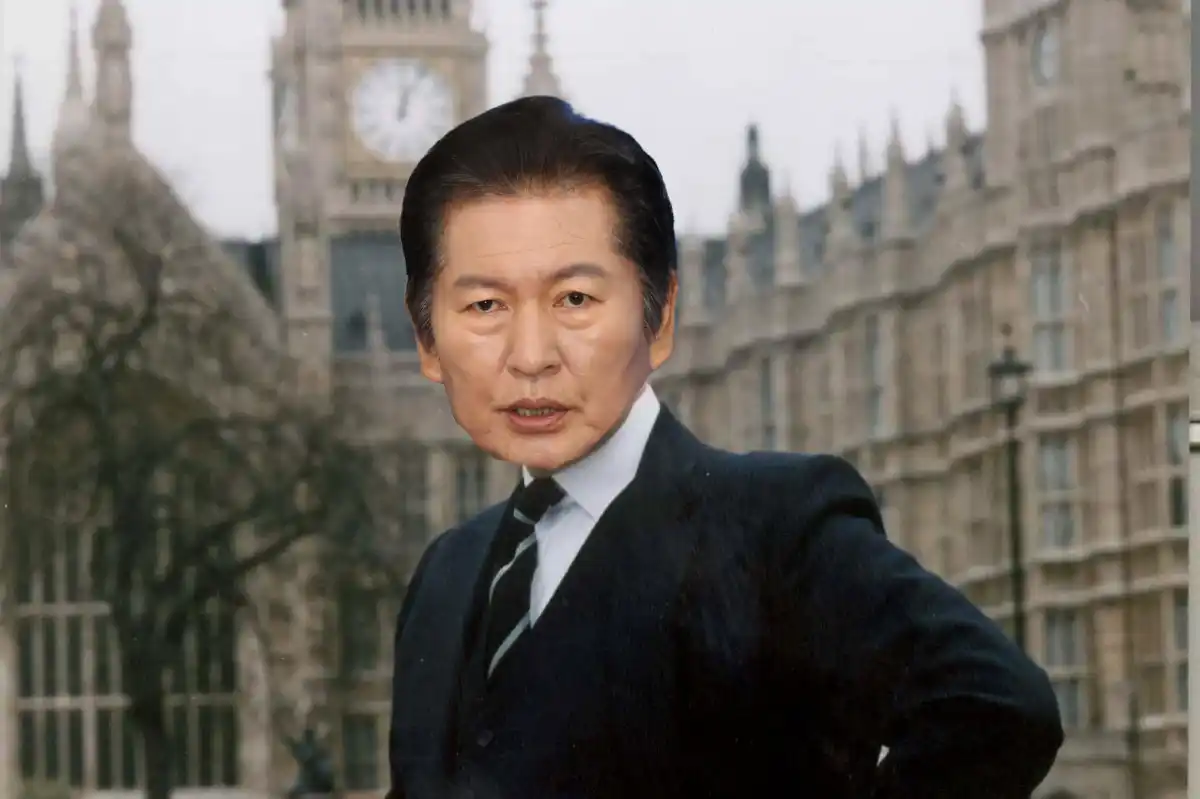

The Statesman Abroad, The Civil War at Home; Unions calling for delaying retirement

APEC summit: President Lee at his best

Why it matters: Lee’s surprisingly adept performance at APEC buys him international capital, but his true test remains domestic: maintaining this newfound statesmanlike grace against escalating internal party challenges.

It doesn’t take long to realize that President Lee carries a chip on his shoulder, specifically regarding his past. In his early political career, he didn’t even try to hide it—he appeared to believe cultivating the persona of an angry outsider would help establish him.

This certainly fueled his firebrand character. During his mayoralty, he didn’t shy away from (literally) wrestling with constituents. On his gubernatorial election day, he famously canceled live interviews mid-broadcast after journalists dared to question him about his scandals.

Has ascending to the nation’s highest office finally sublimated these deep-seated insecurities? So far, it appears so. His demeanor has become far more gracious, despite several notable lapses.

The 2025 APEC summit in Gyeongju highlighted both Mr Lee’s strengths and weaknesses. His lack of experience on the central political stage means he still lacks diplomatic polish. His opening remarks during the summit with US President Donald Trump were a case in point. In front of the cameras, he cited the need to track down not just North Korean, but also Chinese submarines, using this as justification to urge Mr Trump to allow Seoul to build its own nuclear-powered vessels. It was hardly the wisest choice of words given the public setting.

Following the Trump summit, however, Mr Lee appeared to find his footing. His street-smart sense of humor shone when PRC Chairman Xi Jinping gifted him a pair of Chinese smartphones. With a quip rare for stiff Korean political leaders, he caught Mr Xi off-guard—a moment that likely did more to dispel suspicions of pro-Beijing sentiment than any policy speech. I suspect this moment was Mr Lee’s single biggest win, arguably larger than any progress on the submarines.

But the greatest test of character comes at the worst moments. As the honeymoon fades, can Mr Lee maintain his grace in front of the challenges ahead—especially those coming from his own party?

Former President Moon’s YouTube debut as Minjoo infighting intensifies

Why it matters: Moon is effectively abandoning his promise of a quiet retirement—a necessary gamble to rescue his faction’s diminishing political relevance.

Facing the end of his term, President Moon Jae-in often said he wanted to be forgotten and spend his retirement in silence.

His actual retirement has been anything but. He established a bookstore next to his residence in Yangsan, which quickly became a pilgrimage site for ambitious Minjoo politicians seeking the former president’s blessing.

Now, he is starting a YouTube channel. Just as his bookstore was never really just about books—it has always been about signaling; recall when Mr Lee posted a photo with Mr Moon, while Mr Moon notably did not?—his YouTube channel is likely to make more waves in politics than in publishing.

With local elections approaching, Minjoo’s infighting is intensifying. The first notable flare-up is in Busan: a pro-Lee candidate for the Minjoo’s city branch chairmanship blamed the party leadership’s “anti-Lee” sentiment after being cut from the primary, which ultimately elected a pro-Moon candidate. (Local branch chiefs often secure the party’s nomination in elections).

The next arena will be the Seoul mayoral race. The Lee faction has heavyweights preparing to run and will not let the Moon faction take it easily. Although it is unclear exactly where party chief Jung Chung-rae sides, it appears Mr Jung is leaning toward the Moon faction.

The whole picture rather brings to mind Pope Benedict XVI refusing to leave the Vatican even after Pope Francis’s inauguration. Considering his character, I don’t believe Mr Moon wanted this role, but he had little choice. The Moon faction’s talent pool, once deep, has dried up: #MeToo ended the political careers of his two strongest potential successors—and ended one’s life entirely.

The next election will be the last chance for Mr Moon and his faction to identify and cultivate a viable political heir.

“National Governance Stabilization Act”

Why it matters: Lee’s dormant legal risks remain a potent political minefield, with signs suggesting the precarious truce between the judiciary and the executive may soon collapse.

Why the uncertainty regarding where Mr Jung stands? It stems from his actions immediately following the APEC summit.

The party leadership pressed ahead with an amendment to suspend criminal trials against sitting presidents, christening it the “National Governance Stabilization Act.” President Lee had to personally step in to stop it.

In case you forgot, Mr Lee still has multiple legal fronts to fight, and the situation does not look promising for him: the key suspects in the Daejang-dong scandal were handed heavy sentences last week. Minjoo’s push for this Act inevitably raises suspicions about its true intent.

Or… is this Mr Jung pulling a Francis Urquhart maneuver to sabotage Mr Lee?

The Mr Jung I know is rarely capable of such sophistication. I suspect this was rather a failed “balancing” act between Messrs Lee and Moon. It didn’t work, which perhaps explains why he has been a fringe figure for so long.

Given his election victory despite these known legal burdens, the courts should arguably step aside and suspend remaining proceedings for his term’s duration—as they have largely done thus far. Yet both sides have ample incentive to reignite these battles. Conservatives see a tool to undermine the government. And while Mr Lee graciously intervened to stop Minjoo’s overreach this time, his peaceful retirement may eventually depend on just such a shield.

This precarious truce will likely break the moment a politically ambitious judge decides to make their mark.

Why unions call for raising the retirement age

Why it matters: Korea’s rigid labor market and aging demographic are colliding, creating an intergenerational economic conflict that will define future policy platforms.

In France, a president risks his career by trying to raise the retirement age. In Korea, unions demand it.

This has little to do with Confucian ethics and everything to do with the grim reality of Korea’s pension system and labor market. Korea’s net pension replacement rates are among the lowest in the OECD. The seniority system still runs deep in established companies, where firing regular employees is notoriously difficult. Once you manage to secure a spot aboard the gravy train of a major conglomerate, almost nothing can kick you off it.

One way to read this is as generational rent-seeking. The majority “Gen-86,” facing retirement, wants to bend all rules in their favor. They remained silent for years while experts urged pension reform, only to revise the system to their advantage at the expense of younger generations once it was their turn to face the consequences.

Now, they seek to extend their advantage by delaying retirement. Yes, elderly poverty is a serious issue here, but this move seeks to perpetuate their rent from labor market duality, rather than reform it.

The Gen-86 is the single largest voting bloc, and the Minjoo party is well-aligned with their interests. Beyond the retirement age, expect to soon see them pushing to lower the inheritance tax as their parents’ generation begins to die off.

Future populists, left or right, will feed on this widening generational rift.

Words to ponder

However, it is excessive to label it an ‘imperial judiciary.’ The biggest reason is that the judiciary lacks the authority to set agendas. Courts cannot actively seek out unconstitutional laws or administrative acts on their own; they can only render judgments when lawsuits are brought before them. Furthermore, judicial activism arises because politicians and civic groups have dragged the judiciary into the political arena as ‘politics by other means.’ This is because if civic or interest groups conveyed their demands through political parties, if parliament made timely decisions befitting changing times, and if a political culture of accepting outcomes—even amidst disagreement—were established, political issues would not be dragged all the way to the judiciary.

Viewed in this light, the ‘judicialization of politics’—where key national decisions and disputes are resolved through judicial rather than political processes—is merely another name for judicial activism. As party politics declines and partisan confrontation intensifies, actors do not hesitate to file constitutional challenges, submit various applications for injunctions, or even press criminal charges and accusations. Politically motivated special prosecutor appointments are also frequently utilized.

Yang, Jae-jin. (2025). 정부의 원리 [Principles of government]. Mareummo.